Why regulations haven’t curbed U.S. fall fatalities

20 December 2022

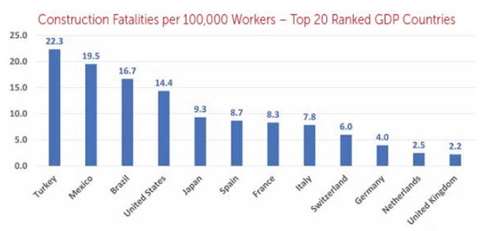

When Sam Reese, with StepUp Scaffold, and co-chair Andrew Smith, with Avontus Software Corp., stepped up to lead the Scaffold & Access Industry Association’s International Council, one of their first orders of business was to compare the construction safety records of the U.S. and the world’s similar economies. The data they gathered suggests that reducing the U.S. construction-industry fatality rate of 14.4 fatalities per 100,000 workers to match the U.K.’s best-in-class rate of 2.2 fatalities per 100,000 would save more than 850 lives every year.

Comparing construction fatality data from countries using ISIC Rev 4 data makes clear that the U.S. falls behind in construction safety compared to other industrialized nations. (Graphic: SAIA)

Comparing construction fatality data from countries using ISIC Rev 4 data makes clear that the U.S. falls behind in construction safety compared to other industrialized nations. (Graphic: SAIA)

Now the International Council is digging into standards, regulations, enforcement, training, certifications and results that countries with lower fall fatality rates are experiencing. The research is intended to inform and improve standards and practices to help America work more safely.

In line with learning from safer systems, the International Council has also recruited global construction-safety experts to share at SAIA meetings insights drawn from their work around the world. Thomas Kramer, P.E., CSP, offered historical perspective on U.S. efforts to reduce workplace falls that identified valuable differences in the ways European countries regulate safety.

Kramer is managing principal of construction engineering firm LJB Inc. He’s also chair of the ANSI Z359.1 and Z359.17 fall-protection-code committees, president of the International Society for Fall Protection and at-large director for the American Society of Safety Professionals and teaches the ASSP Managed Fall Protection Course.

Does fall protection really management risk?

Kramer traces today’s U.S. effort to make work at height safe to the 1995 release of OSHA Safety and Health Regulations for Construction 1926 Subpart M “Fall Protection.” He notes that there were about 100 pages of ANSI standards related to fall protection in 1995.

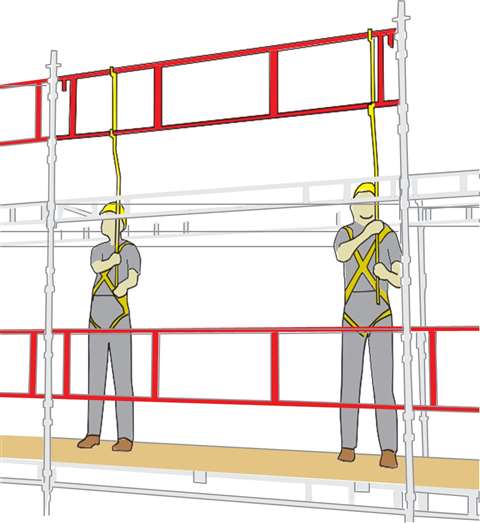

The European Parliament’s work-at-height directive prioritizes collective protection measures that neutralize hazards with alternate processes over personal protection measures. (Photo: SAIA)

The European Parliament’s work-at-height directive prioritizes collective protection measures that neutralize hazards with alternate processes over personal protection measures. (Photo: SAIA)

Since then, three new regulations affecting fall protection have been added and the volume of ANSI standards ballooned to about 1,000 pages. Spending on fall-protection PPE (harnesses and lanyards) has risen 160 percent in last 20 years – it was roughly a $350 million industry in 1995; it’s about an $800 million industry now.

“From 1995 to 2019, the number of serious injuries with days away from work have gone down but fall fatalities have increased 37 percent,” says Kramer. “Fall protection has been the No. 1 OSHA citation for the past ten years. Four or five of the Top 10 (most-issued citations) relate to fall protection.

“The equipment has never been more robust but safety standards focused on durability of fall-protection equipment aren’t reducing fall fatalities. Are we solving problems with robustness of equipment?”

Anchorage points, lanyards and PPE

To illustrate the point, Kramer talks about the evolution of ANSI Z359.1 test of retractable fall-arrest devices. He says the devices were all initially designed for anchorage overhead. He notes how effective they are when used this way. But users increasingly found situations in which they anchored tie-offs at lower points, which changed deployment of the lanyard in an emergency. Equipment would be dropped over an edge, which fundamentally changes the performance of the device.

Standards supported shear-strength tests with the lanyard dropped over an edge, and equipment makers ensured their lanyards would survive tests with a 280-pound weight “to show that it is ‘safe,’” Kramer says.

“But are we just talking about the robustness of the product, or are we talking about a situation in the field? Are we just dropping a test weight, or out there in the field is that actually a human being that’s going over that edge?”

Depending on how close they are to the device’s anchor point, the person in the harness’s free-fall and swing dynamic vary more dramatically when the lanyard is dropped over an edge. It creates additional risk of impact with structure below the fall point.

In contrast, Kramer points out that regulators in the UK – where workplace fatality rates are a small fraction of those in the U.S. – prohibit equipment to be used this way. They don’t think it is fundamentally a safe use.

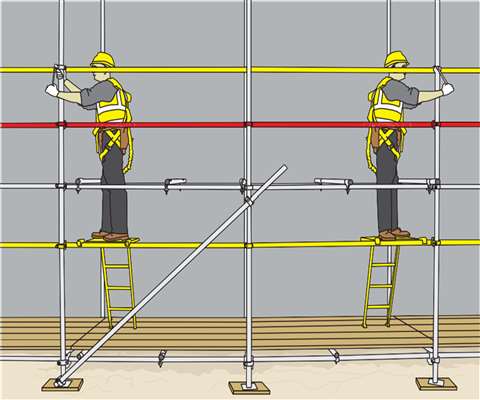

Safety standards of the European Scaffolding Association (UEG) recognize collective protection as a best practice arising from risk assessments done in top safety-performing countries. (Photo: SAIA)

Safety standards of the European Scaffolding Association (UEG) recognize collective protection as a best practice arising from risk assessments done in top safety-performing countries. (Photo: SAIA)

Of course people need reliable PPE, but Kramer says the bottom line is to rely less on personal protective equipment and focus on work processes and system redundancies that eliminate hazards and mitigate risk first, and the PPE and skills training second.

“I think there are some unintended consequences of focusing too much on equipment failure, and not on the fundamental (risk) items,” Kramer explains. “That’s why I go back to (Edward) Deming – the fundamentals of quality focus on the process.”

“Granted, you’re going to have individuals that make bad decisions – sometimes purposefully, sometimes accidentally – but you can’t avoid those mistakes in the field,” Kramer says. We’re human, so mistakes are going to happen. It’s just that when we do make that mistake, are we going to allow it to be a fatality?”

In the near certainty of human mistakes, can you expect that people will be safe relying completely on their consistently proper use of fall protection PPE? Kramer’s point is that equating safe work at height with fall protection skips risk assessments that prioritize work processes that dramatically reduce worker exposure to falls.

“We really need to step back and challenge our industry,” he says. “I think what will happen is that we’ll realize that many times we’re putting people in harnesses and lanyards when they shouldn’t be in harnesses and lanyards.

“In a UK steel-erection project, if somebody’s walking the steel and they could be using an articulating lift instead, they’ll get fined by their HSE (the UK’s OSHA). Over here (in the U.S.) if we see a steel erector in harness tied off on the steel, we’re going to say, ‘Great, they’re using fall protection.’”

Risk assessment spreading across Europe

Another speaker the International Council brought to SAIA is Geir Gule, who as president of the European scaffolding association UEG (Union der Europäi-schen Gerüstbaubetriebe – a name reflecting the German origin of the association founded in 2008) discovered that risk assessment is an industry best practice there.

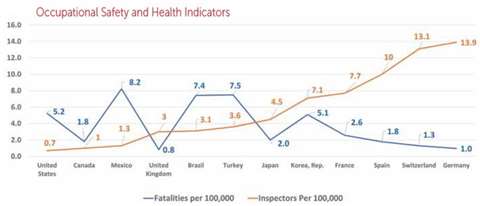

Countries with more safety inspectors tend to have a lower fatality rates. But the U.K.’s fewer regulators and lower fatality rate suggests more stringent regulations – requiring a scaffold contractor to provide a risk assessment, for example – and other factors may impact fatality rates significantly. (Graphic: SAIA)

Countries with more safety inspectors tend to have a lower fatality rates. But the U.K.’s fewer regulators and lower fatality rate suggests more stringent regulations – requiring a scaffold contractor to provide a risk assessment, for example – and other factors may impact fatality rates significantly. (Graphic: SAIA)

UEG members are national scaffolding associations from Germany, the UK, the Netherlands, Poland, Switzerland, Norway, Finland, Sweden, France and Luxembourg. Association goals include influencing legislation developing in the European Union; comparing standards in engineering, training, health and safety; and harmonizing European scaffolding standards.

All scaffolders in Europe are bound by Directive 2009/104/EC of the European Parliament of September 16, 2009. Gule says an important point in this work-at-height directive stipulates that collective protection measures must be given priority over personal protection measures. In other words, mitigating fall risk for an entire crew as part of the work process is a greater priority than fall-protection PPE.

Suppliers are developing advanced guardrail systems and other products and methods to ensure scaffolders can erect and dismantle scaffolding from behind a guardrail. Several countries have included these kinds of collective measures in their regulations but there’s no guarantee these products will satisfy all local jurisdictions.

“There are still differences in the interpretation of the directive in different countries,” says Gule. “This leads to differences in legislation and makes the work we strive to do in UEG somewhat complicated. Our goal is, of course, that we in the UEG can agree on one interpretation and then put pressure on the legislative bodies in the member countries to get one set of common legislation.”

The UEG developed a practical guideline for risk assessment that applies a few principles important to extending safety beyond PPE. The idea is that where hazard exists, risk exists but “hazard” and “risk” are not synonymous. Risk is a function of the severity of harm and the likelihood of the occurrence of that harm. Where hazards are eliminated, risk is eliminated and where hazards exist, risk controls are required.

The UEG’s guideline for risk assessment focuses on:

- Identifying hazards and the risk factors that can contribute to injury or illness

- Assessing risk and contributing factors

- Determining means to eliminate hazards and effectively control associated risk that cannot be eliminated

Gule says, “Risk assessment attempts to answer fundamental questions such as: What can happen under various circumstances, and what are the possible consequences? How likely are the possible consequences to occur? And has an effective level of risk reduction been achieved or is further risk reduction required?”

“In the risk assessment, when you’re deciding on creating access for a particular job, you have to choose the way to provide access to work at height based not only on what equipment you might have available but also what is considered the most-safe method,” says Reese. “And that’s very different. We don’t really have that in the U.S.”

“We have to separate the robustness of the equipment (current focus of U.S. regulation and standards) from the hazards that we’re seeing out there in the field,” says Kramer, “And make sure that workers are properly protected.”

CONECTAR-SE COM A EQUIPE